|

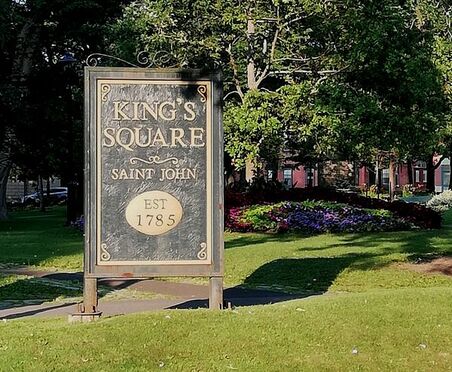

Ron Williams, author of Landscape Architecture in Canada, called King's Square of Saint John, New Brunswick, "one of the most memorable urban squares in Canada." [1] Ian Sclanders in his 1958 MacLeans article called it, "a monument-studded park."[2] The square is both of these things - a lovely space where visitors can stroll and relax and also a site for taking in the province's rich history. The square, established in 1785 and named for King George III, was created just one year after the province of New Brunswick was formed. Early uses included: oxen roasts, militia parades, cricket games, firework displays, public pillories, agricultural fairs and a slaughterhouse. In 1844, the square was developed as a park and its current design was implemented. Orthogonal and diagonal paths were laid out, reminiscent of the Union Jack. The paths meet in a central circle housing a fountain (built in 1851) and a two-storey bandstand (erected in 1908). [3] Williams explained that the square fused two spacial archetypes typical of the 18th century together, namely the place and the square. The place was usually commercial in surroundings and often paved. The square, on the other hand, was typical in residential surroundings and characterized by green space. When describing King's Square he expressed that, "[it] is almost always filled with people, the benches fully occupied. Those out for a stroll, students, people using the park as a shortcut, tourist accompanied by their guide-- all share the space comfortably." [4] The square is a beautiful and quaint spot to visit in Saint John. Making it even more noteworthy are several large monuments dotted throughout, commemorating many different people, as well as local and national events. The Loyalist Cross At the end of the American Revolution (1783) those who wished to remain loyal to the British Crown (known as Loyalists) flocked to British North America, including Saint John and other areas of what became New Brunswick. Approximately 15,000 loyalists settled in New Brunswick during this period. [5] These settlement numbers had convinced the British Government of the advantages of creating a province in 1784, and Brigadier General Thomas Carleton, responsible for transplanting many Loyalists there, was chosen as the first Governor. Tilley Memorial A beautiful memorial for Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley greets visitors at the west end of the square (his actual remains are in nearby Fernhill Cemetery). The monument, erected in 1910, was created by Canadian sculptor Philippe Herbert. Tilley was born in Gagetown, New Brunswick in 1818. He entered politics in the 1840s and had a successful career as federal cabinet minister, Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick, and Father of Confederation. In 1879, he was made Knight Commander of the Order of St. Michael and St. George by Queen Victoria and later made a companion of the Order of the Bath. [6] War Memorial In 1925 a war memorial, sculpted by Alfred Howell, was erected in the square. Howell was born in 1889 in Oldbury, England and studied at the Royal College of Art in London. Once in Canada, he taught at the Toronto Central Technical School. Howell found much success in Canada, creating war memorials in other Canadian cities, including: St. Catharines, Guelph, Sault St. Marie, Oshawa, and Pembroke (All in Ontario). In his book To Mark Our Place: A History of Canadian War Memorials, Robert Shipley stated, "Howell's monuments were often more complex than earlier ones found in Canada," adding they were, "more romantic than the static figures of the previous century." [7] This memorial stands at the entrance to the square as a solemn reminder of those who paid the ultimate sacrifice. Interestingly, its placement was the topic of much debate. Initially, the Women's Christian Temperance Union's drinking fountain (1883) stood in its place, commemorating Loyalist women who founded the city. PhD candidate, Thomas Littlewood in his article, "Conflicting Commemorations: The Saint John War Memorial and the Women's Christian Temperance Union Foundation, 1922-1925," explained that there was a divide in public opinion over the memorial's placement, with many community members wanting to remove the drinking fountain in order to give the war memorial the most prominent spot. Others, including the mayor, strongly felt removing the fountain would be an erasure of history and lead to, "forgetting the city's Loyalist roots." In the end, the war memorial was not placed at the head of the square; instead, it was given a spot nearby. By 1962, the drinking fountain had fallen into disrepair and was removed. [8] The Gorman and Young Memorials The impressive Gorman memorial, built in 1962, captures speed skater Charles I. Gorman, whose leg was injured by shrapnel during the First World War. During the 1920s he excelled in speed skating and was referred to as the "Man with the Million Dollar Legs" and the "human dynamo." Interestingly, he was also a great baseball player. He even turned down an offer to play with the New York Yankees to focus on skating. He participated in both the 1924 and 1928 Olympics, finishing seventh in both. After a lengthy illness he passed away in 1940. At his funeral, thousands of people lined the streets of Saint John to pay their respects. He was later inducted into the Canada Sports Hall of Fame in 1955. [9] Nearby, the Young memorial relates a poignant story of a nineteen year old boy, John Frederick Young, who drowned in 1890 while attempting to save ten year old Freddie Mundee from meeting the same fate. The memorial's plaque has a message from John 15:13, which reads, "[g]reater love hath no man than this that a man lay down his life for his friends." Richard Rubin, columnist for the New York Times stated that the Gorman and Young memorials were "two monuments to men who tried and failed, but went down nobly." [10] Last Alarm Bell Monument The Last Alarm Bell Monument was erected by the Saint John Firefighters Association, Local Union No. 771 and the City of Saint John in order to commemorate the bicentennial of the Saint John Fire Department (1786-1986). Its plaque reads: Dedicated to the memory of those firefighters who answered their last alarm while serving in line of duty, may their sacrifice be perpetuated in everlasting memory by those for whom they serve." In 1877, several years before the Firefighter Association was formed, there was a great fire in Saint John. The fire left 13,000 people homeless. As a result, many people slept in King's Square. Scholar Ronald Rees explained that, "[w]ooden buildings, closely built on commercial and some residential streets, and the ubiquitous tar, ropes, and tindery wood associated with shipping and shipbuilding, all invited flames." Nineteen people lost their lives and 1,600 buildings burned, most of them to the ground. [11] King Square Today In 2013, John Irving and Dr. Richard Currie donated $100,000 for the restoration of the bandstand. 400 people attended the unveiling and the St. Mary's band played, the first band to play there in a decade. Project foreman Andrew Shaw said that, "just watching all the smiles on everybody's faces and all the elderly people that remember the bands that used to play, and watching them play again. It's really exciting to be here. It's a proud moment." [12] The bandstand certainly holds a special place in the hearts of many Saint Johners. 93 year old Marjorie MacDonald recalls, "getting [her] first kiss at the bandstand from a high school sweetheart in 1941." [13] Few places in Canada provide so much local and national history in one small area while also providing a park setting conducive to fresh air, walking, and, when the weather permits, enjoying some sunshine. Strolling through King's Square demonstrates how heritage sites and modern public spaces need not always be at odds with one another; some sites can provide both modern recreation and historical learning. Saint John is a lovely city with a rich history and beautiful architecture. A trip to King's Square is a great way to spend an afternoon and is an absolute must-see! Acknowledgements A special thanks to the staff of the New Brunswick Museum for providing me a copy of the aerial photograph of King's Square. [1] Ron Williams, Landscape Architecture in Canada (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's Press, 2014), 93-94.

[2] Ian Sclanders. "King," Macleans Magazine August 16, 1958. [3] Public plaque in King's Square [4]Ron Williams, Landscape Architecture in Canada, 94. [5] Ronald Rees, New Brunswick: An Illustrated History (Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 2014), 32. [6] Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley - St. John, NB, Canada. Waymarking. (accessed November 27, 2019); P.B. Waite and Carolyn Harris, "Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley," The Canadian Encyclopedia, January 20, 2008 (accessed November 27, 2019) [7] Robert Shipley. To Mark our Place: A History of Canadian War Memorials (Toronto: NC Press Ltd., 1987), 129. [8]Thomas M. Littlewood, "Conflicting Commemorations: The Saint John War Memorial and the Women's Christian Temperance Union Fountain, 1922-1925," Journal of New Brunswick Studies, vol. 10 (2018) [9] Charles Gorman, Wikipedia (accessed November 2019) [10] Richard Rubin, "In Saint John in Canada, Exploring the Legacy of the Loyalists," New York Times, October 27, 2016. [11] Ronald Rees, New Brunswick: An Illustrated History, 151. [12] CBC. Refurbishing King's Square Bandstand Unveiled, August 1, 2013 [13] Shawn Rouse, Saint John's historic bandstand stolen from King's Square, The Manatee, June 23, 2016.

0 Comments

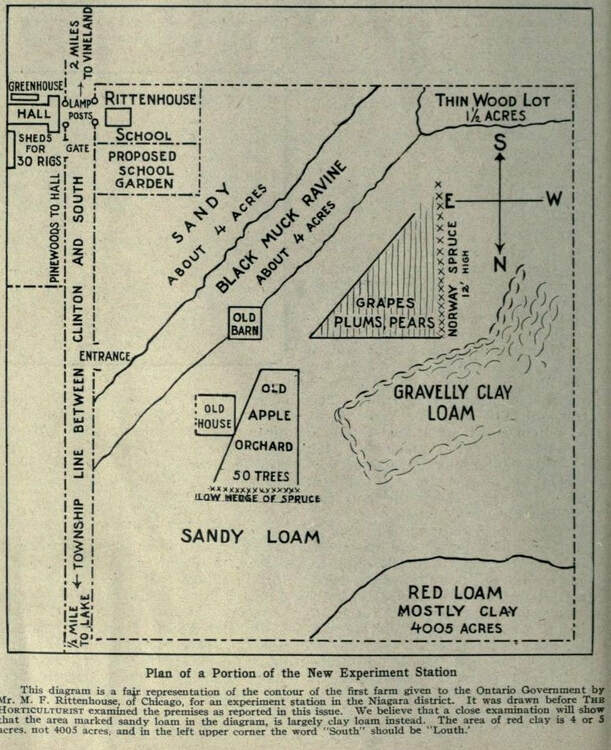

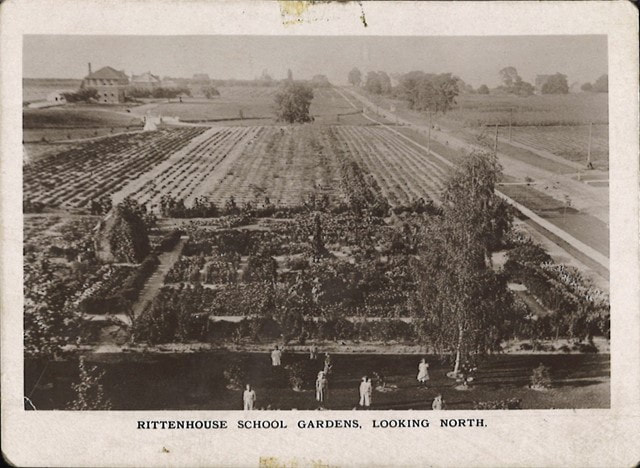

"After all, a lively interest in one’s own environment makes for all that is best in life." -B.M. Winegar [1] In 1885, Donald A. Smith drove the last spike of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), marking the completion of a railway line connecting eastern and western Canada. Shortly after, the CPR worked to beautify railway stations throughout Canada. Shrubs, trees and flowers were planted in an effort to beautify towns along the line. By 1915, they tended to an astonishing 1,500 gardens.[2] Railway Gardens in the West In the 1870s, Canada's first Prime Minister, John A. Macdonald, set forth the National Policy. Initially, this economic policy aimed at protecting manufacturers by placing higher tariffs on imported goods. Over time, the policy changed, recognizing that immigrants were needed to help build the infrastructure that would turn Canada into a great country. It called for the construction of the CPR and settlement of the West.[3] As a result, the CPR developed vast tracks of land in western Canada. In a small way, railway gardens helped fulfill part of the policy's aim by beautifying the prairie landscape in the hopes of attracting new settlers. These gardens were used as advertisements and links to the outside world, showing visitors and those passing through the beauty and fertility of prairie life.[4] Many immigrants found the expansiveness of the prairie landscape daunting. There were few trees, and the land stretched as far as the eye could see. Italian immigrant Luigi Fincati recounted that upon arrival in Canada in 1920, his family took the train from Montreal to Saskatchewan. The family's first impressions of the new country were that it was very vast; they seemed to travel on the train for days, and it felt endless.[5] Many immigrants coming to the prairies had the same impression. Railway gardens were often seen as a welcome and colourful break from the flat landscape.W.J. Strong, a native of Wolseley, Saskatchewan, wrote an article for the OAC Review (1910) expressing this sentiment. He wrote that: If the good work now begun goes on increasing year by year until the Prairie is literally dotted with these beautiful spots, how different will be a journey across the great wheat lands of Canada. Instead of the traveller and settler being wearied with the monotony of huge grain fields and open prairie, they will have, at short intervals, beautiful pictures composed of trees and shrubs, and lawns and flowers, upon which to rest their gaze. Thus their first impressions of this vast prairie country will be so pleasant that they will desire to make their homes here.[6] Royden Loewen, Chair of Mennonite Studies at the University of Winnipeg, argued that the open prairie landscape often required new immigrants to undergo a "mental reorientation".[7] Railway gardens were thus seen as a welcome change of scenery and a taste of "home"; they were used as a symbol for demonstrating the robustness of prairie life. Railway Gardens in the East Railway gardening was prevalent in the West, but it was also practiced in eastern Canada. The CPR was pressured by beautification groups in places like Ontario to create gardens at railway stations. This era was a time when beautification efforts were heavily championed. Vacant lots were filled with flowers, schools created gardens and horticultural societies did various plantings. Considering these efforts, it only made sense that railway stations and lines were beautified in the same way. Much like their western counterparts, people in the East recognized that railway stations were important points of entry; they felt it was important to plant beautiful gardens in order to make a good first impression. B.M. Winegar, representative of the CPR, expressed this view in 1921 when he stated: For the traveler who spends many weary hours on a transcontinental train the sight of a garden is joy. He appreciates our efforts and his ideas of the town he goes through many times are influenced by the appearance of the station and its grounds. Later on he will say, ‘I remember that town, there must be a fine spirit there, the station was neat and the little garden was well kept, and the surroundings attractive.’[8] Railway Garden Creation and Maintenance The earliest CPR gardens were created and maintained by employees who volunteered their time in this pursuit. In 1907, a Forestry Department was created within the company, with a special branch created to take charge of the park and garden work. That year, a nursery in Springfield, Manitoba was established. By 1912, there were greenhouses operating in Fort William, Kenora, Winnipeg, Moose Jaw, Calgary, Revelstoke and Vancouver. From these nurseries, trees, shrubs and plants were distributed to different stations along the rail line.[9]The company also established a Floral Department. In 1911, this department distributed over 100,000 packages of flower seeds to the company's agents, section men, and other employees. A 1911 Globe article explained that: [t]he effective work of the [CPR] Floral Department has had wide-reaching beneficial effects, not only in encouraging a love of flowers amongst its army of employees and in beautifying its long lines of rails, which is highly appreciated by those who travel by the company’s trains, but in showing the world that all corporations are not exclusively after the almighty dollar always.[10] As added incentive, prizes were often awarded to the best gardens. For instance, the 1920 first prize for the "best kept plot" was awarded to the Chalk River Division, where a beautiful garden was kept by baggage man Ed Williams who "devoted his spare time to its cultivation."[11] The outstanding efforts of the CPR and its employees resulted in many beautiful gardens dotting the railway lines, which were enjoyed by the many who saw them.  This Calgary CPR station grew both flowers and vegetables. Many stations during the First World War began growing vegetables to support ongoing war efforts. This photograph is undated, so it cannot be said for sure if this garden was created with these means in mind. Source: Topley Studio / Library and Archives Canada / PA-026186/ Mikan 3424622 Where Did the Gardens Go? Railway gardens were created and maintained until shortly after the Second World War. At that time, Canadian society underwent a rapid transformation. Rural settlement of western Canada began to slow down. Newer technologies and increased disposable income meant that people could now travel more conveniently by car or plane. Railway stations, although still frequented, became seen as less vibrant entry points to the community. It seems fitting to end this post with a quote from Canadian garden historian Edwinna von Baeyer, who said that “[i]n many places where station gardens bloomed, there are now only parking lots.”[12] [1] B.M. Winegar, “Railways and Horticulture” in Sixteenth Annual Report of the Horticultural Societies for the Year 1921 (Toronto: Department of Agriculture, 1922)

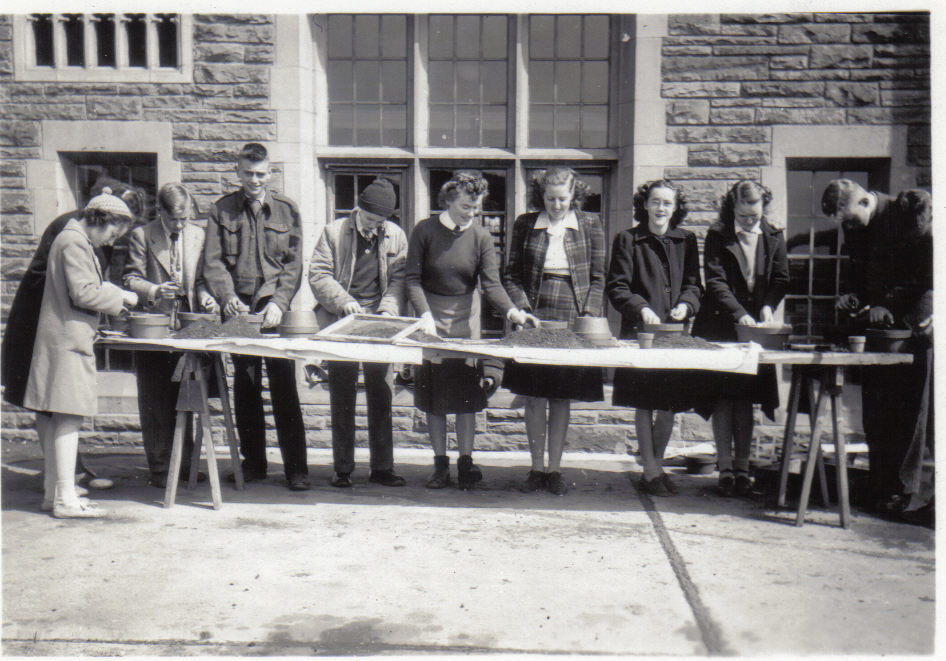

[2] Edwinna von Baeyer, Rhetoric and Roses: A History of Canadian Gardening 1900-1930 (Markham, Ontario: Fitzhenry and Whiteside Ltd., 1984), 26. [3] Donald Grant Creighton, John A. Macdonald: The Young Politician, the Old Chieftain (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), 119-120 [4] Edwinna von Baeyer, "The Rise and Fall of the Manitoba Railway Garden," Manitoba History, Number 31, Spring 1996. [5] Saskatchewan Archives Board, audio tape file number A-307 side A, Fincati, Luigi, interviewed by Anna Maria Crugnale, August 2, 1973. [6] W.J. Strong, “The Beautification of Station Grounds by the Canadian Pacific Railway in Western Canada,” in The O.A.C. Review, Vol. 23, No. 3, December 1910. [7] Royden Loewen, Ethnic Farm Culture in Western Canada, The Canadian Historical Association Canada Ethnic Group Series Booklet No. 29, p. 7. [8] B.M. Winegar, “Railways and Horticulture” [9]Edwinna von Baeyer, Rhetoric and Roses: A History of Canadian Gardening 1900-1930, 25. [10]“C.P.R. Sends Seeds to the Employees,” The Globe, April 5, 1911. [11] Renfrew C.P.R. Station Garden Wins Div’n Prize, The Globe, November 3, 1920. [12] Edwinna von Baeyer, Rhetoric and Roses: A History of Canadian Gardening 1900-1930, 33. At the turn of the twentieth century, businessman and philanthropist, Moses Rittenhouse, funded several projects in his hometown of Lincoln, Ontario, including a school and gardens. These rural children were educated in nature study and natural history, and put theory into practice by learning to grow fruits and vegetables. School gardening taught children valuable life skills, a topic discussed in depth in my previous entry "The Greatest Education-Nature: School Gardening in Canada." The current post explores the history of the Rittenhouse School, with a focus on school gardening. Moses Rittenhouse The Rittenhouse family first came to America in the seventeenth century; they built the first paper mill in the North American colonies in Philadelphia in 1690. Moses' father, John Rittenhouse, was originally from Philadelphia. He moved with his parents to Upper Canada in 1800, settling in Lincoln. Then, in 1846, Moses was born. As a child, Moses went to school in the winter and worked on the family farm in the summer. At the age of eighteen, he left for Chicago, and soon after became a successful businessman. Following in his ancestors' footsteps, he worked in the lumber industry. He was president of the Rittenhouse and Embree Company, and Vice President of the Chandler Lumber Company, the Sixty-Third Street Lumber Company, and the Arkansas Lumber Company. Although he started a new life in America, and a very successful one at that, he never forgot his roots, making occasional visits home throughout his adult years. Rittenhouse donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to Lincoln County as a means of enhancing the rural community. Some of the projects he funded included: the establishment of a lending library (1886); the Rittenhouse School (1890); an addition to the Vineland Cemetery, which included a trust that was to be invested and used for future cemetery maintenance; a gift of land to the government for a horticultural experimental station; the building of Victoria Hall used for public performances; and the creation of a park with a bandstand. He was known to be a very generous man. An article written about him for the American Lumberman stated that “[h]is charitable instincts are largely developed and every act of his life, whether in a business or a social relation, is prompted and controlled by the principle laid down in the Golden Rule.” Moses passed away in Chicago in 1915 at the age of 69. He was buried with his family in the Vineland Cemetery which he helped to fund. Rittenhouse School and Gardens “Education was not so long ago designated by the three ‘R’s’, but to-day a liberal education is demanded, one more properly known by the three ‘H’s’, the Hand, the Head, and the Heart.”-Rittenhouse School Gardens, 1911 The Rittenhouse School was founded in 1890. Moses bore half of its cost and the Globe called the school "one of the finest in the country." The structure was built in the place of the old stone school, of which Moses was a pupil in his youth. With a focus on natural history, the school was equipped with a library (with more then 2,000 volumes), a museum, children's gardens, and a conservatory. Approximately 45 children between the ages of 4 and 10 attended the school each year. The first school gardens appeared on the property in 1907. Teacher Harvey Gayman stated that, “[t]he fact that our school grounds were cared for by a gardener, and the children had little to do but admire the beauty of the flowers and plant life, led to the establishment of a school-garden which was to be theirs, one in which they might experiment, and receive elementary instruction in the principles of agriculture, as a part of their education.” He believed that children in country schools should be taught about farm occupations and economics; school gardening was a wonderful way to get children interested in country life. Around Arbor Day children prepared their individual plots for planting. Plots were 6ft by 10ft for students of the third, fourth and fifth grades. Smaller plots were used for younger students. All pupils were required to use half of their plots for vegetables and the other for flowers. A few months prior to planting, they were given lessons on germination and garden care. They were also responsible for working out their garden plans in exercise books. Gayman explained that "Last year [1910] each child in the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Classes was allowed to plant in his own garden what pleased him best. By this method each child sowed his individuality, and results were quite satisfactory." One year, students performed an experiment with tomatoes. The Ontario Agricultural College supplied students with seeds of 13 varieties of tomatoes, in order for them to determine from a canner's and grower's standpoint which tomatoes were the best. With these seeds, the children planted 480 tomatoes. The Beamsville Canning factory tested the different varieties and it was determined that the Marvel and Ignotum varieties were the best. The students also grew impressive numbers of other vegetables, including 300 celery plants planted in 1911 and 300 watermelons grown annually. Today The Rittenhouse School no longer stands, as both it and Victoria Hall were expropriated for the Queen Elizabeth Way interchange at Victoria Avenue in 1936. Victoria Hall was moved to Prudhommes Landing in Vineland and later closed in 2005 due to structural issues. It sadly burned down in 2008. Although these structure no longer stand, the legacy of Moses Rittenhouse is still felt in Lincoln today. The Rittenhouse Library still exists. In 1969, it moved to a new facility built with money from the Rittenhouse Trust. In 1995 it moved again, this time to a bigger facility, on Victoria Avenue. In 2006, Rita Washko, great-great-great granddaughter of Moses, donated his 1897 desk at the request of her father, Paul Rittenhouse Jr. to the Lincoln Library for their 10th anniversary reception at their new location. The Lincoln Museum had an exhibit to honour the legacy of Moses Rittenhouse in 2006. The Museum's then Director, Helen Booth stated that "Rittenhouse put Vineland on the map as a centre for agricultural experimentation, for education and for just being a pretty town." The legacy of Moses Rittenhouse shows how the effects of philanthropy can reverberate throughout the ages. His projects have positively benefited Lincoln, and are still celebrated today. Acknowledgements Thank you to the staff of the Lincoln Museum for providing me with scanned images and research materials to include in this post. Thank you to Sheldon who kindly gave me his copy of Rittenhouse School and Gardens. [1] "Death has Summoned Vineland Benefactor," the Globe, November 8, 1915

[2] "Ontario School Gets Part of a Fortune," the Globe, November 18, 1915 [3] “The New Experimental Station in the Niagara District,” Canadian Horticulturist, Vol. 29, 1906, p. 171-173. [4] Photographs courtesy of the Lincoln Museum, Library and Archives Canada and the Biodiversity Heritage Library [5] Harvey M. Gayman, Rittenhouse School and Gardens, Toronto: William Briggs, 1911. [6] "Rich History Lost in Fire," Niagara this Week, March 20, 2009. [7] Whatson, "Legacy of Rittenhouse Family Showcased at Jordan Museum," Niagara this Week, June 2, 2006. [8] Lincoln Public Library, "A Brief History of Lincoln Public Library," https://lincoln.library.on.ca/brief_history (accessed March 22, 2019) [9] "Library Donation Opens up Story of Rittenhouse Family," Niagara this Week, September 29, 2006. “Let music swell the breeze, And ring from all the trees, On this glad day. Bless Thou each student band O’er all our happy land: Teach them Thy love’s command, Great God, we pray.” -"Class Day Tree" [1] By 1850, almost all Southern Ontario forests had been cleared, largely as a result of agricultural expansion and timber exploitation by new settlers.[2] Upper Canadian homesteaders had to burn the underbrush of their land, cut down trees, and remove rotten stumps to make way for productive farmland. Southern Ontario's landscape, once lush with forest vegetation, was forever changed. Today, further changes are ongoing. Land is being paved over for housing, strip malls, and parking lots. These changes make it hard to imagine what it would have looked like 200 years or more ago: large forests thick with trees and teeming with animals. In the late nineteenth century, some settlers began to take issue with the vast changes to the landscape. Many began to consider ideas of civic beautification and initiatives to plant trees, flowers, and shrubs in an effort to recapture some of the lost beauty. One such initiative was Arbor Day. Arbor Day was established in Nebraska in 1872. Very shortly after it became popular in other states as well as in Canadian provinces. In 1884, citizens of New Brunswick organized a campaign on Arbor Day, where they landscaped five original town squares in Charlottetown.[3] Quebec began celebrating Arbor Day in 1883.[4] In 1885, Ontario's Education Minister declared Arbor Day a school holiday, so that the time could be devoted to improving and beautifying school grounds through planting flowers, trees, and shrubs. He stated that "the condition of the school grounds throughout the Province is anything but complimentary to our taste and tidiness as a people."[5] Each year school children throughout Ontario had one day off in May to help their teachers beautify school grounds. One teacher, who penned her name as "Girl with the Apron" wrote into the Globe in 1912, detailing how her class spent the holiday. She asked students to bring seeds into class; the response was overwhelming. They spent the day planting nasturtiums, dahlias, hollyhock, gourds, morning glories, asters, poppies, and sweet Williams. She stated, perhaps in a tongue-in-cheek manner: "the arrangements, I'm afraid is utterly contrary to the Ladies Home Journal's ideas of proper color massing. But we'll hope the violent contrasts aren't in blossom at the same time." At the end of the day her class accompanied her on a walk through a nearby forest. Arbor Day concluded with a homework assignment that involved writing an essay on "a ramble in the woods with our teacher."[6] Many people over the years wrote to the Globe arguing about the holiday's importance. Several people took philosophical views, namely that cultivating beautiful things can make for better people. One author, in his 1903 article, expressed that, "what is wanted more than almost anything else is the humanizing and civilizing influence of the beautiful."[7] In 1918, another author asked his readers what could be done to beautify villages and small towns. He then eloquently declared that, "the answers would fill a book, but meanwhile the words 'Arbor Day' float down from somewhere among the gorgeous foliage of the maple trees and write themselves upon the paper and upon the brain and upon the heart."[8] He went on to explain that the maple tree was much more than just a beautiful tree; it was also a meaningful Canadian symbol that instilled patriotic pride. He wrote this during wartime and explained that "in thousands of letters that are crossing the ocean at this moment its leaves are enclosed as symbols of infinite solicitude and affection, carrying messages to sons and brothers and fathers and lovers with an eloquence and pathos that no words could command."[9] Thus, Arbour Day was not just about civic beautification and teaching children about gardening; it also instilled a pride of place in Canadian citizens. Several other writers discussed the importance of Arbor Day through a conservation lens. People were witnessing the disappearance of forests and animals. The landscape was changing before their eyes, and they wanted to preserve and encourage the growth of trees, not just for the aesthetic and educational benefits they could instill, but because tree planting was a means of stewarding the environment. Springs had shrunken and small streams had disappeared as a result of the disappearance of trees. Deforested areas were also subject to cold winter winds, with one writer explaining that farmers feared the effects of this wind every season on crops and orchards.[10] After discussing the negative environmental effects that deforestation had caused, the author explained that "the spirit of Arbor Day should pervade this year [1893]. Children should be taught to value trees and regard them, whether in the school grounds or by the wayside, as silent teachers and companions."[11] In 1915, another author wrote that "the idea of developing trees for the gratification of a future generation is a useful lesson in altruism, and the self-sacrifice involved should be thoroughly understood by those who make it."[12] He felt that planting trees was good for producing shade and improving the climate, and that the removal of trees had contributed to the climate's aridity, injuring plants and animals through a lack of moisture in the soil and air. These writers' statements show that people at the close of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century were thinking about the repercussions of deforestation and saw initiatives like Arbor Day as important ways to get youth to understand the importance of trees and forests in the natural landscape. Beginning in the 1930s people began to write into newspapers expressing their disappointment that Arbor Day was becoming a thing of the past. Concurrently in 1934 the city of Toronto began to record the numbers of tree cutting and plantings. In a later study, City workers uncovered that by the end of 1952, 47,673 trees were removed from streets and parks. During the first seven years of the study 10,640 trees were planted. There were no records of any plantings before 1941, except for a few trees dotting University Avenue and Jarvis Street. [13] A 1953 Globe and Mail article stated that, because of these figures, there was a need for the government to better inform the younger generation of the meaning of conservation, explaining that "it could start in the backyards and on the streets of the city itself." [14] In the past several decades there has been a resurgence in tree planting, perhaps not for some of the poetic sentiments expressed above, but because of links between nature, conservation, and mental health. There has been a burgeoning number of studies and articles linking nature to better physical and mental states. As rampant development continues, Canadians are noticing severe changes to their environment, few of them positive. This development, coupled with increased hours spent in front of screens, takes its toll on our ability to connect with nature. People are beginning to notice an emptiness; many are starting to see the importance of green space and nature's beauty in their own lives. These revelations, along with things such as a celebration of locally produced foods, arts and crafts, etc., have led to an increase in beautification initiatives and nature education. Every September, Canadians now celebrate National Forestry Week. The Wednesday of this week was declared National Tree Day (Maple Leaf Day) in 2011. On this day Canadians are encouraged to plant trees in their communities. Tree Canada, an organization that dedicated efforts to organize the holiday, states that the day serves "as a celebration for all Canadians to appreciate the great benefits that trees provide us - clean air, wildlife habitat, reducing energy demand and connecting with nature." [15] Ontario also celebrates Arbor Week in April/May, Prince Edward Island celebrates Arbor Day on the third Friday in May, and Calgary celebrates the holiday on the first Thursday in May. There are several organizations which support backyard and school yard tree planting and education. Here are a few to check out: Local Enhancement & Appreciation of Forests (LEAF) | Forests Ontario | Planting for Change (P4C) initiative by the Association for Canadian Educational Resources (ACER) | One Million Trees Mississauga | Think Trees Manitoba Forestry Association | Tree Canada Get out there and get planting! [1] The "Class Day Tree" was first published in the New York Arbor Day Circular. I found it in an article written by M.A. Bryant entitled "An Arbor Day Exercise" in the April 1896 volume of the Popular Educator.

[2] Ron Williams, Landscape Architecture in Canada (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's Press, 2014), 93-94. [3] Ibid., 162. [4] Legislative Assembly of the Province of Quebec. Arbor Day: A Few Advices to Farmers on the Planting of Forest and Ornamental Trees (Eusebe Senecal & Fils, 1884) [5] The Globe, April 17, 1885. [6] Arbor Day at School, The Globe, August 3, 1912. [7] Arbor Day, The Globe, March 31, 1903. [8] Arbor Day, The Globe, October 5, 1918. [9] Ibid. [10] Arbor Day, The Globe, March 25, 1893. [11] Ibid. [12] The Significance of Arbor Day, The Globe, April 28, 1915. [13] Toronto's Vanishing Trees, The Globe and Mail, June 6, 1953. [14] Ibid. [15] Tree Canada. "National Tree Day," https://treecanada.ca/engagement-research/national-tree-day/ (accessed February 12, 2019) In 1914, Canadian Grant Lochhead was detained at Prisoner of War Camp, Ruhleben in Germany for the duration of the First World War. Grant had just finished his PhD at the University of Leipzig, but did not succeed in leaving Germany before war broke out. Upon returning to Canada his experiences were recounted in two publications, The Ottawa Naturalist and the MacDonald College Magazine.[1] What was Ruhleben? Ruhleben (German for "quiet life") was a prison camp located at an old horse racing track outside of Berlin, where approximately 5,000 men from Allied nations were interned. At the start of the war, the camp's conditions were poor, but they improved with time as communities within the camp were established. Kenneth I. Helphand, author of Defiant Gardens, described the camp as being "a mud-filed swamp when it rained, cold, with poor latrines and wretched food."[2] German soldiers acknowledged that the prisoners behaved better if left to their own devices; thus the camp was self-governed. The internees created an "English village," where there were tradesmen, barber shops, shoe makers, and carpenters.[3] They even used British street names, such as Bond and Fleet Street. Grant Lochhead's Story When the First World War began, Grant left the Leipzig station for Holland with a group of fellow Britons. Their journey was interrupted by German authorities and the group was taken to a nearby prison. Grant explained that: When we were welcomed by the police officials we were forced to submit to an exceedingly thorough search, and were finally ushered to our cells. To elaborate the feeling one has when the bolt of the cell- door is shot to for the first time is unnecessary, and would only be appreciated by those who have done time.[4] One week later he was given a pass to leave. While on board a train to Holland (for the second time) Grant was arrested at a station near the Dutch border. He was then taken to the Schloss Hotel where eighty men - consisting of Britons, Frenchmen, Russians, and Belgians - were kept in two rooms under heavy guard by German forces in the hot month of August. Two weeks afterward he was taken to a military prison in Hanover, where "one did have the luxury of a cot to one's-self."[5] After one month's stay, he was brought to a camp where the Germans held detained Alsatians. After only one week in the Hanoverian prison, he was liberated by the American consul, at which point his belongings were returned, with the unfortunate deduction of "one mark and fifty pfennig per day for 'board and lodging.'"[6] For one month he and the other liberated men lived in the town under strict police supervision. Then, on Nov. 6th, a general order was issued stating that British subjects in Germany were to be interned at Ruhleben in retaliation for England's harsh treatment of German prisoners. For the duration of their stay at Ruhleben, internees slept in a sparsely furnished horse stable. Grant remembered that, "in the course of time much work was done by the prisoners themselves in endeavoring to make their quarters a little more habitable."[7] He also mentioned that those in England were helping to feed the camp by sending weekly food parcels. The parcels were a much welcomed form of aid, especially since the camp's menu offered meager and bland rations. Grant explained that: The official menu was simple and the daily allowance meager — one-fifth of a loaf of bread, coffee substitute for break- fast, soup for dinner, more coffee substitute with an occasional slice of sausage of doubtful derivation for supper.[8] Another internee wrote about the food in his journal lamenting, "Cabbage soup again, third time in seven days."[9] Grant also spoke of the diverse population of internees, ranging from, "mercantile marine illegally detained with their ships before war was actually declared, [...]students, business men, jockeys, trainers, tourists over on a week's holiday trip, and men representing occupations.." [10] and that: One can easily imamine [sic] the little domestic squabbles which might arise when a musician, a jockey, a fisherman, a bank manager, a theological student and a horse-dealer found themselves living together in a space 4 yards each way. All the while, however, a settling process was evident, and kindred spirits gravitated slowly together so that finally congenial people arranged to live together in time. [11] As mentioned above, the camp's internal affairs were left to the prisoners, making it self-governed (to a point). When prisoners realized they were to remain there for a long time, they created committees and clubs, ranging from drama and gardening, to art. A community garden was tended with the intent of growing vegetables for consumption. In 1916 the Ruhleben Horticultural Society was formed and membership reached 943 men.[12] They procured many seeds from the Royal Horticultural Society in London. They also brightened up the camp by growing: lobelia, pyrethrum, begonias, antirrhinums, godetia, and many other beautiful flowers.[13] Internees also taught each other physics, chemistry, and biology in laboratories. Grant explained that: The worst feature of life in such a place was not to be found in the physical discomforts and annoyances, but in the dull, unending monotony of life with the uncertainty which over-shadow- ed everything — this and the enforced in- activity when our fellow-countrymen were doing so much outside. [14] Grant's former botany professor, Tubeuf, sent his student microscopes and other equipment for use while he was a prisoner.[15] For Grant and the other prisoners, their liberation came as a surprise; when they received word of their freedom they were carrying on with "life as usual." They were rehearsing the Christmas play when the news arrived that they were to be freed. Grant returned to Canada, where he had a successful career as the Head of Bacteriology at the Central Experimental Farm in Ottawa.[16] Further Reading For researchers interested in learning more about Grant Lochhead and his time at Ruhleben you can visit Library Archives Canada, where they have a fonds consisting of his thesis, journals from 1914-1972, and photographs of the prisoner of war camp. Click here to learn more. [1]Unknown Author, "Microscopy and Biological Activities at Ruhleben" The Ottawa Naturalist, Vol. XXXII, No. 5, November 1918; Grant Lochhead, "Experiences in German Prison Camps," MacDonald College Magazine, Vol. 9, No. 3: February-March 1919

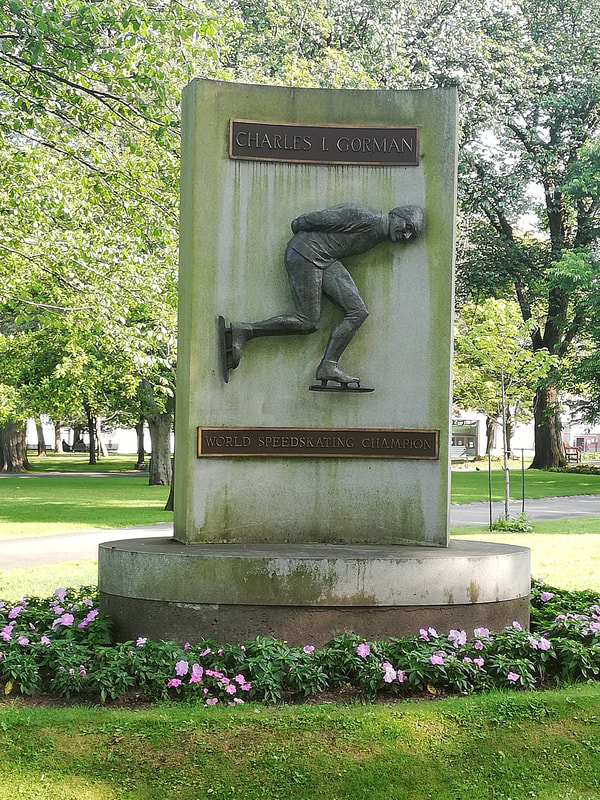

[2] Kenneth Helphand, Defiant Gardens: Making Gardens in Wartime (San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 2006) 114. [3] Ibid. [4]Grant Lochhead, "Experiences in German Prison Camps," MacDonald College Magazine, Vol. 9, No. 3: February-March 1919 [5] Ibid. [6] Ibid. [7] Ibid. [8] Ibid. [9] Elgin Strub-Ronayne, "Cabbage soup again"-the hardships & resilience of men held in Germany's Ruhleben prison camp', in John Lewis-Stempel, Where the Poppies Blow: The British Soldier, Nature, The Great War (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson), 219. [10] Grant Lochhead, "Experiences in German Prison Camps," MacDonald College Magazine, Vol. 9, No. 3: February-March [11] Ibid. [12] John Lewis-Stempel, Where the Poppies Blow: The British Soldier, Nature, The Great War, 221. [13] Ibid. [14] Grant Lochhead, "Experiences in German Prison Camps," MacDonald College Magazine, Vol. 9, No. 3: February-March [14]Royal Horticultural Society Lindley Library, "Ruhleben Horticultural Society," https://www.rhs.org.uk/education-learning/libraries-at-rhs/events-exhibitions/ruhleben-horticultural-society [15]B. Elliott. "A Tale of Two Societies: the Royal Horticultural Society and the Ruhleben Horticultural Society In the Occasional Papers from RHS Lindley Library, Volume 12, September 2014, Horticulture and the First World War Were a kind fairy to suggest that I might have one wish granted, it would be that I would like to see every child given an opportunity to have flowers, birds and animals, a place to play, a garden in which to work, and something all his own to love."-J.A. Taylor [1] A Brief History of School Gardening Newton Wiley's 1912 Globe article highlighted the successes of school gardening, stating that "in Ontario during the last four or five years a remarkable development along educational lines has taken place that has been little heard of outside of the centres affected. It has consisted in a broadening of the public school curriculum to a wider utilization of the greatest education-Nature."[2] At the turn of the twentieth century there were several programs that focused on teaching children gardening. In 1904 Nature Study was established as a course at the Ontario Agricultural College (OAC), with the purpose of improving the aesthetic side of rural life in Ontario.[3] Through this program, rural boys and girls were prepared for farm life, where they believed this was "nature's own method of training her children."[4] That same year, Montreal philanthropist Sir William Macdonald initiated and funded a school gardening program. Under the directorship of James W. Robertson, Dominion Commissioner of Agriculture and Dairying, the program commenced. Twenty five schools - five for each province - were selected in Ontario, New Brunswick, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island.[5] The program allowed for selected teachers to be sent to one year nature study programs, funded by Macdonald, in places like the University of Chicago, Cornell, the Ontario Agricultural College, and Columbia University. To support future teacher training Macdonald donated $175,000 to Ontario to build what is now known as the Macdonald Institute at the Ontario Agricultural College.[6] Macdonald School Gardening and Nature Study were very popular and successful initiatives that brought students and their teachers closer to nature through practical application. These programs came to a close with the beginning of the First World War, but there was a silver lining. Ontario Horticultural Societies took up the torch where these programs left off. Individual societies throughout the country encouraged children to garden. A ten year old girl who tended a school garden in the Windsor area stated: I grew in [my garden] vegetables, such as radishes, beets, carrots, onions, beans, tomatoes and turnips; all of which grew very nicely. Some of my vegetables I canned after having been shown the way to do them and took them to the Windsor Fair, and got a first prize for $3 for 1917.[7] Another little boy participated in a horticultural society gardening contest and his proud teacher stated that: At the end of the season he got a prize, 75 cents. They sent it to him in the form of a cheque, which the parents had framed, the father saying if they cashed it for him the money would be gone, but they could show the framed cheque to their friends.[8] School gardens were an important part of children's education at the turn of the century. Teaching children to garden instilled many important values. The next section will discuss some of these skills and values, showing how people thought about gardening at the turn of the century.  Teaching in Komarno School, Man. (garden making with students) 1917 Source: Library and Archives Canada/George E. Dragan fonds/a088420 Teaching in Komarno School, Man. (garden making with students) 1917 Source: Library and Archives Canada/George E. Dragan fonds/a088420 What was the Value of School Gardens? As discussed above, school gardens meant more than just learning to garden, and students reaped more than just plant knowledge. In 1903, Professor W. Lochhead of OAC wrote an article for the Canadian Horticulturalist magazine where he answered, "what is the value of school gardening?" He believed that it: (a) Inculcates habits of order, care, neatness and method and forces the child to constant observation. (b) Brings the mind into closer communication with nature (c) Teachers and scholars are brought closer in touch (d) Physical recreation of a helpful pleasurable nature is provided (e) Provides a hobby that may keep many from less desirable occupations during their leisure time (f) A greater interest is taken in garden work in the community (g) Indirectly, a love for home and its environments is created (h) Gives boys and girls the rudiments of an industrial training which may be of value later in life.[9] This insightful list shows that there was far more positive skills learned by students than just producing vegetables. Below we will explore these, and other virtues that school gardening taught children in detail. Citizenship and Nation-Building School gardening made good citizens. It was thought that, "through the work of the school garden the pupil of either the country or city school is made a better student and a more useful citizen. "[10]Thus, school gardening was used as a nation-building tool. The act of gardening connected students with the land around them, making them prideful of where they lived. Professor Lochhead illustrated this idea when he stated, "there is no more civilizing influence anywhere than that of the school gardens, and history tells us that one of the greatest advances in the history of the race occurred when men began the cultivation of plants, he then became a home builder, and gave up his wondering, nomadic habits."[11] Gardening also taught children many different skills. One such skill was discussed during the First World War when food production became a patriotic way of helping Canadian and Allied troops. J.A. Taylor expressed that, "school gardens also contribute to national prosperity. We know that the cost of vegetables [is] exceedingly high. It is nothing but right that the children should be taught to play their part in national prosperity."[12] Gardening, then, taught children about economics and enlisted them to help in the war effort. Character Development Through Moral Education School gardening also made good children. George D. Fuller, Director of the school in Brone Country, Quebec, said that gardening had a very positive effect on students because their attention "turned to a consideration of the beautiful to the exclusion of many baser thoughts."[13] Essentially, students spent more time on the virtuous activity of gardening than on activities that might get them in trouble. Thus, it was determined that school gardening in cities usually meant a decrease in crime. In St. Thomas, for example, it was reported that there were fewer juvenile court cases after school gardening was put into the curriculum, because children were busy tending gardens.[14] In addition, active horticultural society member Mrs. R.B. Potts believed that school gardening instilled empathy in Canadian youth. She believed that, "people of all nations are recognizing as a truth that knowledge is for man a means to an end; true education is based on sympathy for fellow man and a widespread appreciation of nature, best gained through observation and continued self activity."[15] Better Students School gardening also made better students. Garden historian Edwinna Von Baeyer stated that "absenteeism, always the bane of the rural school, decreased as the students rushed to school to see if their beans were up yet."[16] Not only did students spend more time in school, but the ones who gardened typically received better grades than those who did not. J.A. Taylor believed this to be the case because, "school garden help[ed] to furnish an environment in which their characters are to develop and grow. Environment forms a large amount of life's course of study, and its enrichment makes noble tastes, refined ideas, elevated thoughts and lofty ideals, and sweetness of soul."[17] A Progressive Idea? Students learned about the environment around them by going outside and gardening. They made mistakes, suffered disappointment, felt pride, and had their curiosity for the outside world satiated. John G. McDonald of the Aurora Horticultural Society explained that, "it is a recognized principle that we learn by doing. So in school gardening nothing will awaken an interest in this subject so much as getting to work at it."[18] This practical application of education is an early example of the progressive educational model. The progressive educational movement began in Canada after the First World War. At this time people re-examined the values of existing, traditional values against innovative ideas. This movement promoted active and personal learning opportunities for pupils by encouraging them to learn through more hands-on experiences. This type of education emphasized life-long learning that taught students to be socially responsible, democratic citizens.[19] Gardening was a way for children to get outside and "learn by doing." Engaging in gardening made them lifelong students who became good Canadian citizens. School Gardening Today School gardens are still in use today, although the way we think about these gardens has changed. Earlier gardens took on the Victorian ideals of crafting moral and just children. Today, school gardening focuses on teaching children more about conservation and respect for the environment. Marjorie Harris, garden columnist for the Globe and Mail, stated that "the sooner you teach a child the joys of the garden, the more likely you'll have an adult who respects the environment."[20] Engaging in school gardening also helps children stay active. In 1996, Nancy Lee-Collibaba of Royal Botanical Gardens called out to parents, "are you looking for some interesting activities that will keep the kids away from computer games or TV, or provide skills to enrich their minds? Introduce your children to gardening!"[21] Gardening is not in the school curriculum, and programs depend on individual teachers' interest in the subject. In 2000, Ossington-Old Orchard Public School's garden, which had fifty students tending it, was threatened with removal when the school could no longer fund the instructor. Grade five student Alex Dault-Laurence was dismayed at the news, stating (perhaps with help from his parents) that, "if the garden disappears, part of the school's identity disappears too."[22]There is a successful school garden at Humewood Community School in Toronto, where students are encouraged to design their own garden plots. The project's coordinator, Alex Lawson, said that "when I saw the students' designs--their wide range of plant choices, their lively sense of colour--I was impressed."[23] In British Columbia there is a popular program called Farm-to-School, which matches participating schools with farmers in order to help teach students more about where their food comes from.[24] There are also many programs outside of schools which provide children with garden education. Royal Botanical Gardens has had children garden plots since 1947. The idea of the plots was initiated by Barbara Laking, the wife of then Director Leslie after her visit to the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, which had a child gardening program in place.[25] When explaining the value of the gardens, Brian Holley of RBG stated that one of the objectives of the plots was "to provide the children with knowledge. The educational opportunities that a garden makes available are almost unlimited. In addition to gardening techniques, students are instructed in botany, cooking, flower arranging, crafts, and natural history."[26]RBG's child gardening plots are still very popular, and more information about their program can be found here. Many horticultural societies continue to support junior gardening throughout the country. There are also other initiatives to get children gardening, like the Junior Master Gardener, Lucy Maud Montgomery Children's Garden of the Senses, Children's Eco Programs, Spec School Gardening Program, Evergreen's Weekend Nature Play in the Children's Garden, High Park's Children's Garden, and so many more! [1]J.A. Taylor, "The Influence of School Gardens on Community," 12th Annual Report of the Horticultural Society for 1917 (Toronto: Department of Agriculture, 1918), 50.

[e][2] Newton Wiley, "School Gardening in Ontario," The Globe, June 15, 1912. [3]Ibid. [4]Alexander M. Ross, A College on the Hill: A History of the Ontario Agricultural College, 1874-1974 (Toronto: Copp Clark Publishing, 1974), 73. [5] Edwinna von Baeyer, Rhetoric and Roses: A History of Canadian Gardening 1900-1930 (Markham, Ontario: Fitzhenry and Whiteside Ltd., 1984), 40. [6]Ibid. [7]J.A. Taylor, "The Influence of School Gardens on Community," 49. [8]Ibid. [9]W. Lochhead, "School Gardens," The Canadian Horticulturist, July 1903, 273. [10]Newton Wiley, "School Gardening in Ontario," The Globe, June 15, 1912. [11]W. Lochhead, "School Gardens," The Canadian Horticulturist, July 1903, 246. [12]J.A. Taylor, "The Influence of School Gardens on Community," 31. [13]Edwinna von Baeyer, Rhetoric and Roses: A History of Canadian Gardening 1900-1930, 42 [14]J.A. Taylor, "The Influence of School Gardens on Community," 29. [15]R.B. Potts, "School Children and Horticulture," 8th Annual Report of the Horticultural Societies for the Year 1913 (Toronto: Department of Agriculture, 1914), 54. [16]Edwinna von Baeyer, Rhetoric and Roses: A History of Canadian Gardening 1900-1930, 42 [17]J.A. Taylor, "The Influence of School Gardens on Community," 48. [18]John G. McDonald, "School Gardens," 14th Annual Report of the Horticultural Societies for 1919, 89. [19]John Elias and Sharan B. Merriam. Philosophical Foundations of Adult Education (Krieger Publishing Company, 1995) [20]Marjorie Harris, "Students Watch how their Garden Grows," The Globe and Mail, May 16, 1992 [21]Nancy Lee-Colibaba, "Gardening with Children: Cultivating Enriched Children," Pappus, Summer 1996, 24-25. [22]Theresa Ebden, "Please Save our Garden, Student Pleads," The Globe and Mail , May 11, 2000 [23]Marjorie Harris, "Students Watch how their Garden Grows," The Globe and Mail, May 16, 1992 [24]Jessica Leeder, Farm-to-School programs boosts the health of B.C. students and the food economy, The Globe and Mail, October 11, 2011 [25]Brian Holley, "Gardening with Children-Sowing Seeds for the Future," Pappus, Summer 1985, 9-10. [26]Ibid. Spreading their Wings: Fred and Norah Urquhart’s Search for the Monarch Butterfly Wintering Ground1/18/2018

Every summer, monarch butterflies fill Canadian skies, dancing from flower to flower. They offer us inspiration, nostalgia for childhood, and visual reminders of nature's beauty. For these reasons, and many others, they have always been of interest to Canadians. In a 1906 Globe and Mail Article an unknown author exclaims:

Who does not know the Monarch, with his great, bright, reddish wings, bordered and veined with black, and decorated with two rows of white spots.[1]

Apart from their striking appearance, much about monarchs' lives remained a mystery, especially their migratory patterns. At the turn of the century people speculated about this phenomenon, wondering where monarchs went during the winter months. In 1916 another author posited they must winter in a warmer climate, stating:

For the first time during a ten years' residence in Canada I saw the trek or migration of the "Monarch" butterflies (Ansola plexippus) to a warmer climate...when one thinks it over one cannot help marvelling that the migratory insect should be so strongly developed in such an apparently frivolous race as the butterfly.[2]

Seven years later another author speculated that monarchs seemed to travel from the south during the springtime, explaining that:

From June until October one may often see the Monarch butterfly flitting about over fields and meadows...these butterflies come from the South in the spring or early summer.[3]

These statements show that people at the beginning of the twentieth century understood that monarchs were indeed migratory insects and that they flew south for the winter. But where did they go? Dr. Fred Urquhart wanted to find out the answer.

Dr. Fred and Norah Urquhart

Like many Canadian children, Fred Urquhart loved catching butterflies. The difference between Urquhart and other children, though, was that his childhood activity turned into his lifelong work and passion--finding monarch butterflies' wintering spot. "I've always been hot on butterflies" he said in a 1976 Globe and Mail article, stating that: As a kid I spent my summers bumbling around with a butterfly net. There was a man in our town who had a large butterfly collection and when I wasn't chasing butterflies, I was pouring over his books. One day I read about the monarch, about how no one knew where it wintered. That got me going. I had planned to be a musician. Instead I became an entomologist.[4]

Fred became the Head of the Life Sciences Division and Curator of Invertebrates at the Royal Ontario Museum. He also taught Zoology at the University of Toronto. During the late 1930s he began trying to figure out where monarch butterflies overwintered.

But how does one track monarchs? Tagging their wings seemed to be the answer. It took Dr. Urquhart five years to develop a tag that could be adhered to monarchs' fragile wings. He "tried everything," stating that he tried: painting the wings, punching holes in the wings, even glueing on tags: but nothing seemed to work. With the gluepot we just ended up with a sticky mess of butterflies glued together.[5]

When he painted the wings he commented that, "it just looked like they had flown into a freshly painted fence" and that he "quickly scratched that approach."[6] By 1940 he started to use paper stickers that worked as long as a patch of scales on the wings were scraped off.[7]

Just before the Second World War began, the research director at the University of Toronto would not let Dr. Urquhart include his project in the annual report "for fear the government would think we were doing nothing but running around chasing butterflies."[8] During the war years, his quest remained on pause, but after the war ended, his search continued. In 1945, he married Norah, a sociologist whom he recruited into his monarch search. At first she wasn't too keen on butterflies, but soon admitted that she had, "grown to love the little things" and that she "might not have found things so easy if they'd been ugly little insects."[9] In 1952 Dr. Urquhart and his wife published an article in Natural History magazine which discussed their tagging problem and asked for volunteers. Letters poured in and the Urquharts began sending volunteers labels which read, "Send to Zoology University Toronto Canada."[10] To study these butterflies, the Urquharts spent a lot of time around sewage disposal plants collecting larvae. These areas were great places to look because monarchs lay their eggs on milkweed, which tends to grow in damp places. "People think it's all such pretty work," Dr. Urquhart stated, "I think they have this mental picture of Norah and I perpetually gamboling through the meadows with our butterfly nets looking romantic. What we really do is spend a lot of time in miserable places."[11]

The couple continued to develop new labels. They successfully created one that would stick in any condition. These tags were half an inch (1.27 cm) wide and one inch (2.54cm) long. Half of the tag folded over the leading edge of the front wing and included an address and an individual code.[12] Now that they had better labels, the Urquharts furthered their cause, putting out 3,000 news releases about their project, resulting in many people wanting to help.[13] To trace the migration, Dr. Urquhart said that he got assistance "from about 600 people-high school students, housewives, lawyers, doctors- anyone from age 12 to 84."[14] In 1957 nine-year-old Fred Jacob of Wickford Rhode Island mailed a small package containing a monarch butterfly with a tagged wing to the Urquharts.[15] Lloyd Beamer of Meaford, Ontario, a retired science teacher, was one of Dr. Urquhart's most devoted volunteers in Ontario.

Initially, the couple believed that monarchs wintered in Florida, so they set up several research stations throughout the state. By 1966 this hypothesis resulted in a dead end. "We did get returns" he said, "but there just weren't enough to account for all the migrating butterflies of Eastern Canada and the United States."[16] In 1970 at Norah's urging, Dr. Urquhart wrote an article in a Mexican newspaper, asking naturalists to look for monarchs. Kenneth C. Brugger, an American Engineer stationed in Mexico, responded to the article saying that he had seen a dead monarch on the ground. Dr. Urquhart said: When Mr. Brugger wrote to us that he had seen many dead butterflies along the back roads while travelling in his camper van, I felt certain we were close to a discovery.[17]

At the beginning, Ken did not know much about monarchs. Norah explained that "he kept sending us specimens that didn't remotely resemble the monarch! But we couldn't have had a better research assistant."[18] While Ken got better at identifying the butterfly he married a Mexican woman, Cathy Aguado, who was also a butterfly enthusiast. The couple showed a monarch specimen to local loggers who said they had seen those exact butterflies in the mountains.

On January 9, 1976 Kenneth called the Urquharts' from Mexico, telling them that he and Cathy had found the overwintering colony in the Sierra Madre mountains. He described large masses of monarchs covering evergreen trees in a 20 acre area.[19]Unfortunately, Dr. Urquhart was in the hospital at the time of the discovery and had to wait another year to see this phenomenon for himself. When he made the trip one year later he exclaimed: my heart was pounding so hard we had to stop every few feet and gasp for air. The air was terribly thin and the way in very difficult. We're not young people anymore and I keep thinking 'my God, imagine getting this far and dying before I ever see the things!'[20]

When he did finally see what he had been searching for he beamed, that:

there were probably 30,000 butterflies on every branch. There were so many a branch broke from the weight of them and crashed to the ground as we stood there watching. You couldn't take a step without crushing them. Everywhere, those glowing wings. I felt paralyzed.[21]

Making the story even more amazing, among those that fell from the branch was a butterfly with the label, "Send to Zoology University of Toronto Canada."[22]

One of the monarchs that Karin Davidson-Taylor, Education Program Officer at Royal Botanical Gardens, tagged and released last year. Karin is a member of the Monarch Teacher Network of Canada, an organization of educators and nature enthusiasts who teach people about monarchs through hands-on training and experiences.

Species at Risk

Thanks to Fred and Norah Urquhart and their team of researchers we now know the wintering location of the monarch butterfly; however, this overwintering phenomenon might one day be something of the past, as these butterflies are now a species at risk. Even sadder is that the decline in monarch numbers is not specific to this species. Many other plants, animals, and insects in North America (and the world) are experiencing declining numbers due to the destruction of their habitats. There are several reasons why the monarch is faced with dwindling populations. Chip Taylor of Monarch Watch, a not-for-profit organization based out of the University of Kansas that helps track monarchs, states that a big problem lies with: our insane desire to make everything look like our front lawn and mow and use herbicides along all our roadsides- that has eliminated a lot of monarch habitat.[23]

Monarchs lay their eggs on milkweed and many factors have contributed to the elimination of this key piece in the monarch life cycle. For one thing, milkweed is considered a noxious weed in Canada.[24] Farmers and gardeners actively remove it from their properties. Changing farming practices in the United States’ Midwest have also resulted in a large decline of the plant, more specifically in the Corn Belt region where increased cultivation of genetically modified soybeans and corn has greatly impacted milkweed numbers. When these genetically modified crops are planted the fields are sprayed with large amounts of herbicides in order to wipe out other crops. More and more land is being used to grow corn in order to create ethanol, turning once fallow lands - perfect for monarch breeding into highly sprayed croplands.[25] Increased Mexican logging has also led to the destruction of the monarch's overwintering habitats.[26]

All three countries: Canada, the United States, and Mexico are working to ensure that proper conditions are met to make stable milkweed populations, and sufficient breeding grounds.[27] In 2014 the monarchs’ breeding area shrank by 44% from the previous year. “The result is the lowest since conservationists began tracking monarch winter populations…” said Omar Vidal, director of the World Wildlife Fund Mexico. He went on to state that, “if we don’t take immediate actions, we are very close to losing this migratory phenomenon.[28] In 1995 Canada and Mexico formed an agreement to provide more research and better monitoring of the species.[29]

What can you do to help?

One of the easiest ways to help monarchs is to plant milkweed in your backyard. Please check with your local nursery that the plant has not been sprayed with pesticides. If it has, it will kill caterpillar populations. You could also plant nectar-producing plants in your yard, like salvia and mint. Lastly, donate or volunteer with organizations that are working hard to help our little friends. Here are a few good places to start: Monarch Teacher Network of Canada | Journey North | Mission Monarch | Monarch Watch | Save our Monarchs | The Monarch Joint Venture | Live Monarch | The Monarch Foundation | World Wildlife Fund Canada | Monarch Larva Monitoring Project |

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Karin Davidson-Taylor, Education Program Officer at Royal Botanical Gardens for loaning me her personal book on monarchs, providing me with names of organizations, and teaching me about these wonderful insects. Also, thank you too Bill Kilburn from the Back to Nature Network for teaching me to stop and appreciate the natural world, reminding me of how complex and beautiful it really is. And also a big thank you to ProQuest for making digital copies of the Globe and Mail accessible and easy to search for. Last but not least, thanks to Adam Montgomery for proof-reading this post!

[1]Unknown author. A Midsummer Carnival of Butterflies, The Globe, September 15, 1906

[2]Unknown author. The Trek of the Butterflies, The Globe, September 30, 1916 [3]Unknown author. The Monarch Butterfly, The Globe, August 25, 1923 [4]Carson, Susan. The Lost Kingdom of the Monarchs, The Globe and Mail, October 2, 1976 [5]William, Shannon. The Monarch Man Keeps Searching, The Globe and Mail, July 30, 1976 [6]Carson, Susan. The Lost Kingdom of the Monarchs [7]William, Shannon. The Monarch Man Keeps Searching [8]Carson, Susan. The Lost Kingdom of the Monarchs [9]Ibid. [10]Ibid. [11]Ibid. [12]William, Shannon. The Monarch Man Keeps Searching [13]Ibid. [14]Unknown author. Migration Traced: Monarchs Gather for Journey South, The Globe and Mail, September 11, 1973. [15]Unknown author. Tiny Tags Help Trace Butterfly Migrations, The Globe and Mail, August 16, 1957 [16]William, Shannon. The Monarch Man Keeps Searching [17]Ibid. [18]Carson, Susan. The Lost Kingdom of the Monarchs [19]William, Shannon. The Monarch Man Keeps Searching [20]Carson, Susan. The Lost Kingdom of the Monarchs [21]Ibid. [22]Ibid. [23]Hammer, Kate. Flying Alongside a Royal Migration, The Globe and Mail, October 8, 2012 [24]Matas, Robert. "Canada, Mexico to Nurture Butterflies," The Globe and Mail, October 18, 1995. [25]Boychuk, Evelyn. Monarchs' Decline Driven by Milkweed Loss, The Globe and Mail, June 5, 2014 [26]Semeniuk, Ivan. "Monarch Butterfly Numbers Dwindle to Lowest Ever," The Globe and Mail, January 30, 2014. [27]Mittelstaedt, Martin. "Monarch butterflies can’t Get by on a Wing and a Prayer," The Globe and Mail, July 1, 2008. [28]Semeniuk, Ivan. "Monarch Butterfly Numbers Dwindle to Lowest Ever," [29]Matas, Robert. "Canada, Mexico to Nurture Butterflies," Our gardens and our environment deaden or brighten our souls.[1] -Annual report of the Horticultural Societies, Department of Agriculture, 1908. In 1955 Elsinor Burns, member of the Canadian National Institute for the Blind (CNIB) building committee and an executive member of the Garden Club of Toronto (GCT), had the idea of creating a fragrant garden outside of CNIB's headquarters to be enjoyed by the blind. She was joined by Lois Wilson, Gardening Editor for Chatelaine Magazine, who was also a member of the GCT, in spearheading the project. The club voted to raise $400 ($3,684.51 in 2017) for the project. Astonishingly, they raised $21,000 ($193,436.82 in 2017). A committee was created consisting of five GCT members, as well as five blind members of the CNIB, in order to create a beautiful, but equally important, functional garden that could be enjoyed by those who were sight impaired. The garden, located on Bayview Avenue, was "set on a gently rising hilltop in the geographical centre of Toronto, circled by the buildings of the National and Ontario headquarters of the Institute, it [was] an acre of gardens planted with fragrant flowers, scented herbs, shrubs and trees, blooming from earliest spring till frost."[2]  Image courtesy of the Centre for Canadian Historical Horticultural Studies at the Royal Botanical Gardens. Image courtesy of the Centre for Canadian Historical Horticultural Studies at the Royal Botanical Gardens. More than one hundred types of plants made up the plant list. "Most [were] fragrant by wafting their perfume far on the wind as lilacs and apple blossoms do, or by having their leaves bruised as with mint and lavender. Others [were] chosen for their sweet, close-up scent like carnations and sweet William."[3] Several plants were included because of their interesting tactile qualities like, woolly rabbits' ear and furry old man's beard. Pine trees were chosen for making a "lovely sound in the wind," while other plants were picked because they encouraged the nesting of songbirds.[4] "Whispering aspens rustle[d] in the wind; petunias and geraniums abound in the raised beds, their petals ready for the seeing hands of the sightless; such plants as artemisia feel like long-piled rugs; and the scent of thyme, mint and other herbs linger[ed] in the air."[5] Many people helped put this project together. Scientists came to analyze the soil. Professors of botany suggested fragrant plants to include in the garden space. Landscape architects worked extensively with the blind to ensure that the garden was laid out in a manner that could be fully enjoyed by the latter. More than an acre of the garden was framed around its outside edge by a rectangular exercise walk that was 700' wide. The asphalt surface of the walkway changed to wood slats as it approached the corners as a way of indicating to the walker that it was time to turn around.[6] In 1957 a blind resident of the CNIB stated, "all we residents at Clarkwood [residence of CNIB] take a daily walk around the garden just to see what has happened there each day. The blind need something to hang onto physically, such as a cane or an arm of a friend, and we have found the garden something to hang on to in a different sense."[7] Completed in 1956, the garden was enjoyed by the nearly one thousand blind and partially sighted people living, working or visiting the centre every day. It was the first garden of its kind built in Canada, and one that came to be recognized throughout the rest of the world. The GCT copied their plant lists for others who were interested in creating a garden for the blind.Their records indicate that they sent their lists to Australia, South Africa, Chile, Brazil, the United States, and other Canadian cities. Art Drysdale, a well-known Canadian horticulturist, mentioned that in 1974 the park director in Budapest, Hungary showed him their fragrant garden . Their department had contacted people in Toronto because "the best such garden is there." He also mentioned a similar experience occurring in New Zealand in 1983.[8] In 2002, the CNIB began construction on the property, which resulted in part of the rose garden being removed. Then, sadly, in 2004 the rest of the garden disappeared as "the balance of the land [was] developed into condos and upscale townhouses."[9] There were talks about making a smaller fragrant garden. The author found no other records indicating what transpired of the project. [1]Department of Agriculture, Third Annual Report of the Horticultural Societies of Ontario for the Year 1908, (Toronto: Ontario Department of Agriculture, 1909), 10.